Step 7: Assess Climate Change Risk

The approach and the associated needs of climate change information for climate change risk assessments may vary depending on the context, especially the depth of the assessment. Therefore, it is always essential to establish the context first when determining climate change information needs (step 2). That step defines the purpose and the scope of the assessment, the relevant climate change information to be used, how the risk assessment will be conducted and so on. Following that, and after finding climate information (step 3) or constructing climate change projections (step 6), the assessment can be undertaken in three broad activities: identifying, analysing and evaluating risk.

This step provides an overview of these three key activities. More detailed information can be found in the Australian Government’s climate change impact and risk management guide for business and government[1], which is a good example of a climate change risk assessment procedure that is compatible with the international risk management standard ISO 31000:2009.

Key activities

Identify the risk

Identifying climate change risk is identifying how climate changes impact on each of the elements of the sector, location, community or other matter of interest for the assessment. This can be done by simply describing and listing what may happen and how.

This activity requires some initial understanding of the links between the current climate and the matter being assessed. It also often requires knowledge of critical thresholds of which the degree of change could lead to the onset of the consequence.

For example, studies show that banana, a staple food in Papua New Guinea, is sensitive to extended periods with temperature beyond the 20–30 oC range[2]. If the frequency of temperatures above 30 °C is projected to increase in Papua New Guinea due to climate change then there could be significant impacts on banana productivity in the future.

Likewise, engineering specifications for the construction (location and design) of critical coastal infrastructure such as public buildings, ports, roads, bridges and drainage systems need to factor in climate change related risk from rising sea levels and more frequent and/or intense extreme rainfall events to avoid impacts of flooding, storm damage and/or erosion over the effective life of the investment.

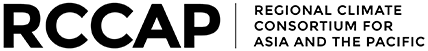

The links between climate change and associated risk may be direct or indirect, and may also include non-climate factors such as population growth and urbanisation of communities. The example in the following figure shows that the risk to a municipal water company as a provider of clean water supply in a city may not arise directly from changes to climate variables, but from a chain of consequences that affect water supply and demand. There may also be coincident risks to the energy sector through impacts on electricity consumption/demand.

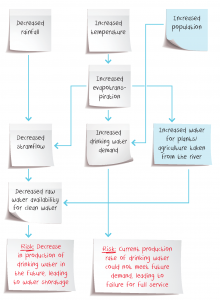

Drawing a causal diagram that shows the links between climate change and risks for key elements of the area of interest can be a useful way to identify risks. The following is an example using clean water supply as the area of interest.

Risks can also be identified by undertaking a literature review and by brainstorming in a workshop or focus group with people who already hold basic knowledge, such as agricultural extension officers or engineers. If this activity has already been conducted when determining climate change information needs (step 2), then the list of the identified risks may just need to be validated or re-affirmed with relevant stakeholders (e.g. banana growers, urban water supply manager, consulting engineers, disaster risk managers) and edited as appropriate.

Analyse the risk

The main purpose of this activity is to determine preliminary levels of each of the identified risks.

Risk can be analysed qualitatively (e.g. in a workshop) and/or through quantitative analyses, depending on context of the risk (e.g. country, sector, time period, other non-climate factors) and the scope of the assessment (i.e. initial, rapid or detailed assessment).

Assess the consequences of each identified risk to the sector of interest. Take into account any existing factors that will control the risk, such as the existing practices which people can adopt to mitigate impacts as the climate changes, and other non-climate trends that could happen at the same time and which might somehow modify the effects of the risk.

Next, form a judgment about the likelihood of each identified risk, assuming that each of the climate change scenarios being considered arises.

Combine the consequences and the likelihood to determine the level of risk (or risk rating). For example, if extreme high rainfall has a low probability of occurrence in the region but it has high potential consequences (e.g. urban flooding, landslide, disruption to water supply production due to flood and heavy soil suspension in raw water caused by the landslide, powerline disruption), the risk of water supply failure associated with projected increase in extreme high rainfall could be rated as moderate to high.

Evaluate the risk

If more than one risk has been identified and analysed, rank the risks in terms of their severity. The ranking should consider and reflect confidence in the climate change projections used, for example, if there is confidence that some scenarios are less likely to occur than others.

Screen out minor risks that do not require further attention and identify those risks for which more detailed analysis and/or immediate adaptation is recommended. This should be carried out together with the relevant stakeholders.

Once ranked, the judgments and estimates of the risk should be re-affirmed. This can be achieved by discussing results with relevant sectoral stakeholders (e.g. farmers, fishers, extension officers, climate change advisors/coordinators, water supply managers, engineers, NGOs).

The following example shows an application of this approach.

CASE STUDY EXAMPLES

[1] Australian Greenhouse Office, 2006. Climate change impacts & risk management: a guide for business and government. Department of Environment and Heritage, Canberra, 74 pp. Available at http://www.environment.gov.au/climate-change/adaptation/publications/climate-change-impact-risk-management

[2] McGregor A, Taylor M, Bourke RM, Lebot V. 2016. Vulnerability of staple food crops to climate change. Vulnerability of Pacific Island agriculture and forestry to climate change. M Taylor, A McGregor and B Dawson. Noumea Cedex, New Caledonia, Pacific Community (SPC): 161–238.